The Flywheel of Disruption

Disruption is happening more rapidly and more fiercely than ever before. Unlike past disruptions, which involved broad, fundamental technology diffusion, more recently we are seeing emergent change resulting from layered and combinatorial evolutions of technology and society.

Disruption is happening more quickly and more forcefully than ever before. Unlike past disruptions, which involved broad, fundamental technology diffusion, more recently we are seeing emergent change resulting from layered and combinatorial evolutions of technology and society.

Unprecedented technological change

The industrial revolution unleashed a series of technological changes of a magnitude that had never been seen before. Electrification, plumbing, antibiotics, the combustion engine, and the telephone resulted in significant transformations of our society.

Yet looking back at those changes, it’s easy to wonder whether the pace of change recently has been slowing. How can we compare mobile phones to urban sanitation? Or personal computing to electrification? Recent technologies arguably haven’t resulted in changes as fundamental as their industrial precursors.

But the fact is that we are in a period of unprecedented technological change—albeit one that’s meaningfully different and thus difficult to understand using frameworks rooted in the past. These changes are fundamental and far reaching.

Where are the flying cars?

Peter Thiel famously said “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” So where are the “individual flying platforms” predicted by Kahn and Wiener in their 1967 book, The Year 2000?

"We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

Professor Robert Gorden at Northwestern argued in his 2016 book that the five Great Inventions between 1870 to 1970—electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication—were far more fundamentally transformative than anything that has come since.

“The outlines of most of the inventions that are going to change life are fairly clear now for the next 25 years. I’m not saying innovation is over, what I see is that it’s incremental and slowly advancing along fewer dimensions of life than the great changes between 1870 and 1970.”

— Robert J. Gorden

He bolsters his argument by pointing to a drop in average US GDP per capita growth from 2.0% in the mid-20th century to 0.9% more recently. According to his assessment, key inventions in the late 19th century manifested as technological change over time, peaking between 1920 and 1970. He believes it has been long enough to say that the IT revolution won’t amount to much real improvement in our lives.

So, it’s settled then—the pace of technological change is slowing, right? Not so fast.

Hindsight bias and rice on the chessboard

Gordon’s focus on per capita growth may obscure broader developments, including substantial improvements in quality of life, entertainment, and other improvements that may not be accurately reflected in per capita GDP. Importantly, those benefits may be more substantial now than in the past.

He also seems to lump most modern technology into a single concept: information technology (IT) with a few callouts to the Internet and personal computing. It’s clear he thinks of technology innovations as fairly discrete and easily discerned.

I think it’s far more complex than he makes it out to be. The innovations of our age are manifesting differently, and perhaps the real impact of information technology has yet to be felt in full force.

A different manifestation

Whereas electrification, sanitation, and similar technologies were large and fairly discrete, modern technologies are more layered and complex. Modern innovations build on each other as they disseminate through our economy and society, leading to disruptions that can be hard to predict and surprisingly far reaching.

As we’ll discuss later, disruption involves human organizations changing systems—industries, businesses, society, our economy.

Take, for example, Airbnb. The business model above is in essence a high level description of the system that Airbnb created. Each of the elements is interconnected. Changing one part would have implications for other parts of the system. And the complexity of the elements obscured by simple circles that each represent complex and interdependent sub-elements of the system.

As is typical, multiple technologies were required in different parts of the system to unlock disruption opportunities. Many of the elements of the system relied on a combination of technology diffusion through society and consumer and organizational behavior changes. All of those changes require time. And all of it together makes predicting the nature and timing of disruption very difficult.

One question venture capitalists ask persistently is, “why now?” Successful disruption can be as much about timing as anything else. A good answer typically requires bringing together many interconnected threads that have led to a new window of opportunity.

Gordon’s Great Inventions paved the way for information technology and many other innovations, which in turn helped usher in a world that is increasingly complex and interconnected. That makes predicting the future of disruption a very different matter than it was before.

Entering the inflection point

The Economist quotes Ray Kurzweil, who describes an old fable about a gullible king who is “tricked into paying an obligation in grains of rice, one on the first square of a chessboard, two on the second, four on the third, the payment doubling with every square.” At first, the numbers are small. But only by halfway through, the king is out 100 tons of rice. And it gets worse—quickly.

Technology increasingly builds upon itself in ever more complex ways that are extraordinarily hard to predict. This “exponential technology extrapolation” can take time to manifest at scale. But like the rice grains on the chessboard things can suddenly begin growing at a shocking pace.

“Roughly a century lapsed between the first commercial deployments of James Watt’s steam engine and steam’s peak contribution to British growth. Some four decades separated the critical innovations in electrical engineering of the 1880s and the broad influence of electrification on economic growth.”

— Has the ideas machine broken down, Economist 2013

In other words, it’s unlikely we have seen the full impact of the technologies that started emerging in the 1980s (e.g., microprocessors and personal computing) and have continued to emerge in waves (mobile phones, cloud computing, etc.) with increasing rates of market penetration.

The many smaller innovations (and disruptive startups) disseminating through our economy are creating self-reinforcing loops by opening new opportunities that continually feed into each other. The result is a flywheel of disruption that’s moving at an increasing speed. Increasingly, the flywheel is moving faster than enterprise planning and execution cycles can react to. That has created an important opening for faster, more agile startups.

Canaries in a coal mine

In the late 19th century and into the mid-20th century, companies such as General Motors, Bell Telephone, General Electric, and Carnegie Steel leveraged new technologies to create powerful defensive moats that lasted for decades. But that no longer appears to work.

Now even the largest and most successful organizations face an existential threat, as evidenced by the decline in average tenure on the S&P500 from 70+ years down to 12. Over the past decade major companies such as Sprint, J.C. Penney, Frontier Communications, Office Depot, Kodak, and the New York Times have left the S&P 500. In 2017 alone, 27 companies were dropped from the index.

Not only have massive enterprises succumbed, but entire industries have essentially disappeared: yellow pages, map makers, video / DVD stores, open outcry traders, and photofinishing. Newspapers, bookstores, electronics retailers, and more are likely on their last legs. What do they have in common? They all succumbed to new technologies.

I think Credit Suisse had it right in a 2016 report that said:

“We argue that disruption is nothing new but that the speed, complexity and global nature of it is. In fact, it is clear that a number of sectors are currently impacted by multiple disruptive forces simultaneously.”

Foster and Kaplan surely believe that things are different (from their book “Creative Destruction: Why Companies That are Built to Last Underperform the Market—and How to Successfully Transform Them”):

"The current apocalypse—the transition from a state of continuity to a state of discontinuity—has the same kind of suddenness. Never again will American business be as it once was."

It certainly seems that large successful companies are facing some sort of existential threat. What is driving this? And where is it heading?

From atoms to bytes

Bill Gates describes the importance of concepts introduced by Haskel and Westlake about the difference between tangible and intangible investment:

"Microsoft might spend a lot of money to develop the first unit of a new program, but every unit after that is virtually free to produce. Unlike the goods that powered our economy in the past, software is an intangible asset. And software isn’t the only example: data, insurance, e-books, even movies work in similar ways."

— Bill Gates

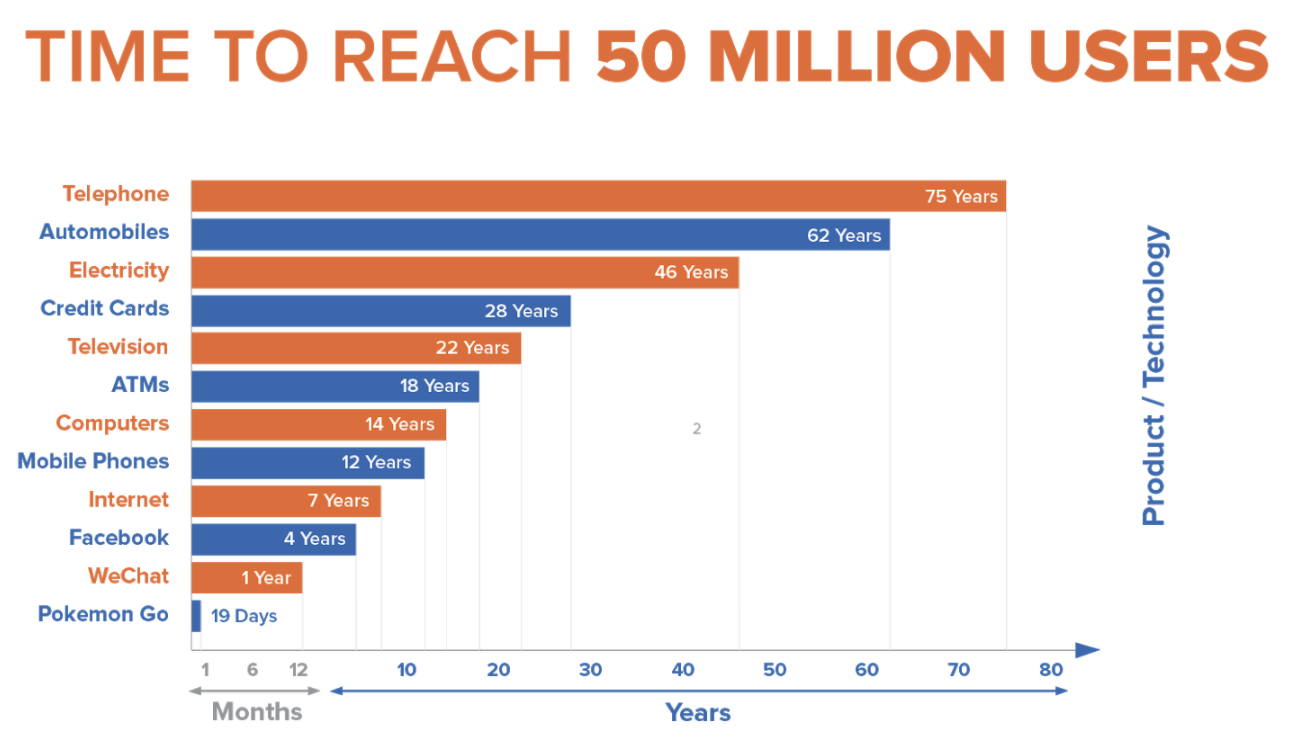

Evidence supporting this can be found if we look at the speed of diffusion for new technologies and products. The time to 50 million users by innovation:

This sort of speed is only possible in the context of intangibles. Gates believes the “portion of the world’s economy that doesn’t fit in the old model just keeps getting larger.” As you’ll see below, one of the reasons for this evolution is the continued layering of new technologies which in turn open the door to newer innovations.

This means that the assets which so often defined enterprise value aren’t as valuable as they used to be, and their place is being taken by intangibles. As consumer tastes and market dynamics continue to change more quickly, having assets will become a liability.

A declining reliance on hard assets makes it easier for new entrants to disrupt. It also means that value becomes harder to measure and more ephemeral—concepts that are largely alien to established enterprises. It also plays havoc with enterprise planning cycles. Upstarts with better insights, agility, and speed can achieve extraordinary scale in less time than it takes for most enterprises to even register that it’s happening.

The Social Era

Kastelle et al. suggest there is an additional (or related) change driven by a fundamental shift in the basis of firm advantage they describe as the advent of the Social Era:

"We have observed the economy move from one where centralized organizations initiated value creation to one where that same value creation develops with the help of multiple outside, contributing networks. This tectonic shift means that all modern industries now have a different source of advantage … starting in the 1990s, when influencers enabled innovation platforms as business models, and continued to what we see today in the Social Era with crowdsourcing, open innovation and business models."

They condense their finding in the same document, saying "If the industrial era was about building things, the social era is about connecting things, people, and ideas." (emphasis added).

What’s important here is that the very nature of value creation has changed. Large scale assets are less relevant in the social era, and in fact often represent a loadstone that holds organizations back from adapting to this very different new world.

"The social era is about connecting things, people, and ideas"

Changing nature of work and the firm

Ronald Coase established a theory of the firm focused on balancing efficiencies of internalization vs externalization of assets. He identified three key costs of doing business:

- search and information costs

- bargaining and decision costs

- policing and enforcement costs

He contended that transactional costs determine whether resources should be internalized (part of the firm) or externalized. Firms grow as they internalize capabilities for which transactional costs justify doing so.

Information technology continues to drive down the transactional costs of all three areas identified by Coase. This creates a natural push towards externalizing resources and thus diminishing the size—and relevance—of a firm.

This is further exacerbated by social evolutions—perhaps driven by other factors such as increased information liquidity and social transparency—that result in many working age people demonstrating lesser interest in working for a big enterprise.

Historically, firms have also derived competitive advantage from their proprietary knowledge repositories. But the democratization of knowledge with the advent of the Internet and search engines has dramatically weakened any such advantages. And while modern enterprises often sit upon massive troves of data, the vast majority still struggle with turning that data into insights. They have thus lost another key advantage that has traditionally accrued to the firm.

All of these factors have destabilized even the largest firms, leading to a weakening bond between enterprises and their employees. The notion of a job for life is gone. Employees may identify with their employer, but in the modern era the bond is much more tenuous than ever before.

As the pace of modern change continues to accelerate, enterprises increasingly find that technology cycles move faster than planning cycles ever could, making firms seem even less relevant. In fact, some argue that the time of the firm has come and gone:

"If computer technology has the capacity to simplify and streamline transaction costs, more and more work can be done through these smart-contract arrangements, making traditional human-managed firms obsolete."

— “What’s the purpose of companies in the age of AI?”, HBR

I make related argument in my post of The Age of Protocols, suggesting that decentralized cryptographic protocols may render firms largely obsolete.

Globalization and urbanization

The rise of China (and other inexpensive manufacturing hubs) has threatened manufacturing in developed countries for at least forty years. Now, globalization, driven by communication and transportation technology, is impacting virtually every industry. Even local industries—for example via e-commerce—are impacted by the increasingly global nature of our economy.

Globalization has also impacted consumer attitudes through a combination of increased exposure to divergent views, as well as new expectations for price, quality, and variety. And the pace of dissemination is occurring ever faster, with trends spreading around the globe almost instantly. Take, for example, fast fashion which has reached a point where new styles hit stores within a few weeks of being recognized. That’s a far cry from the 1800s fashions that often took years to spread across the globe.

Urbanization has resulted in an increasing number of educated and higher income people living together in close proximity, leading to cross pollination of ideas and preferences at unprecedented scale. And with increased scale comes a natural desire to express individuality. When that desire is coupled with global visibility, it drives many consumers towards new modes of self-expression and individualized preferences sought in an effort to achieve differentiation and self-actualization.

Altogether, this leads to a series of implications for the market. It is becoming much more difficult to predict what consumers will want in the modern economy. These shorter preference cycles often occur more rapidly than the decision making and operational cycles required for organizations to act upon them.

Consumer attitudes

We have already discussed how consumer attitudes—particularly their speed of evolution—have been impacted by globalization and urbanization. Yet the evolution of consumer attitudes is more than about speed and individuality. Consumers have adopted new attitudes that are often foreign to existing industry players based on their understanding of “how things work.”

Take for example, Citibank, which as recently as 2016 argued robo advisors were not interesting to high net worth individuals. And yet, a survey found that 22% of ultra high net worth people would consider having 100% of their assets managed by a robo advisor, with many more considering allocating a portion of their assets to them. As of 2019 robo advisor assets under management have been growing at over 100% per year and are at almost $1 trillion AUM. And a good portion of those assets belong to high net worth individuals.

Consumer expectations are increasingly lofty as well. As new technologies proliferate, the feasibility of delivering customers what they want on their terms and timeline is increasingly possible. The rise of the on-demand economy is a perfect example with extraordinarily broad implications for everything from what and how they buy, to how much time they have for other things, to their attitudes towards automobile ownership, and more.

Another consumer trend that has broad implications for our economy is the transition from assets to experiences. New generations in particular are placing far more emphasis on experiences such as travel and dining and less on owning stuff. An asset light existence gives them the flexibility to change their geography, tastes, and more much more quickly. That has significant implications for economic models leading to a new rental economy. Our portfolio company, Nickson Living, for example, will furnish your apartment down to the wine glasses at the click of a button for a monthly fee, and then move it out after you do.

Other forces meanwhile are diminishing the power of brands through a combination of consumer attitudinal changes and the rise of direct-to-consumer business models. Together these represent an existential threat to even the largest consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies along with their channels and partners.

"It’s a whole new game in consumer packaged goods. The combination of digital technologies, new competitors with vastly different economics, and consumers who enthusiastically incorporate multiple shopping approaches into their everyday lives."

— Digital Insurgents, Emerging Models, and the Disruption of CPG and Retail, BCG

Rise of the startup economy

Most of the world was first introduced to the notion of venture backed startups in the 1990s with the dotcom boom. After a few stutters (the dotcom crash and the financial stress of 2008), startups have roared back (to the extent they ever really receded). Venture capitalists have been pouring billions of dollars every year (over $84 billion in 2018) into startups aiming to disrupt existing industries.

Over the past twenty years it has also become much easier and less expensive to launch a startup. Advances in entrepreneurial thinking (e.g., Steve Blank), combined with distributed services and infrastructure (e.g., AWS, open source, DevOps tools) have had a dramatic impact on the volume and quality of startups that succeed, while lowering their average cost to start. Social attitudes towards entrepreneurship have changed, too, with an increasing number of young (and not so young) people interested in and willing to embark on an entrepreneurial career.

The extraordinary scale of the startup economy means that only a small percent need to survive to result in substantial market disruption. And this is only the beginning. As alpha leaves the public markets, it has landed in the private markets. The flood of capital in the late stage private markets (think Softbank) has skewed returns. Now, one of the few remaining places to find real alpha is in early stage private companies. That’s why more and more capital will continue to flow into disruption.

Emerging transformational technologies

Microprocessors and miniaturized data storage enabled the personal computer. The personal computer and modern communications technology enabled the Internet. The Internet, cloud computing, and open source enabled software-as-a-service. Each of these—and many more—further enabled new sets of enabling technologies that further rely on each other.

Altogether, these enabling technologies contributed to globalization, changing consumer attitudes and behaviors, the rise of the social era, and frankly most of the fundamental changes we have discussed so far.

But what might be less obvious is where all of this might be heading. These enabling technologies are starting to give way to much more transformational technologies.

Just a few emerging and upcoming technologies worth mentioning:

- Decentralized cryptographic protocols

- Augmented reality and virtual reality

- Quantum computing

- 3D on-demand manufacturing

- Molecular / biological manufacturing

- Synthetic foods

- Next generation robotics and cybernetics

- CRISPR / genetic modification

- IoT / ubiquitous computing

- Autonomous vehicles

- Personal flying vehicles

- Local power generation

- High density energy storage

These technologies—enabled by developments dating back to the 1980s—will truly transform our society, economy, and world in ways that it’s hard to predict but that will certainly be fundamental. And the pace of change involved will likely be much faster than anything the world encountered during the industrial era.

I was fascinated a few years ago to hear my son (then 13) answer the question, “what do you want to be when you grow up?” He responded without skipping a beat, “how do I know? Most of the jobs by then don’t even exist today.”

Layered on top of these transformational technologies are a set of broader social and physical changes that are likely to have meaningful impacts on infrastructure, communities, and people worldwide. Examples are the educational bubble and the rising cost of education; climate change and rising sea levels; the end of the fossil fuel era and its geopolitical implications; and the significant infrastructure overbuilding in the face of the transition to e-commerce and on-demand delivery.

Technology driven changes in the workforce are likely to create further upheaval. The US workforce was 84% farmers in 1810. Today it’s around 2%. That happened fairly gradually—and still resulted in meaningful dislocations. The emerging technologies we’re talking about will likely occur much more quickly. We could face huge levels of structural unemployment in the next 10-20 years, and the repercussions from that are hard to predict beyond the fact that they will be substantial.

The burden of knowledge

A corollary of all the changes we’ve mentioned is the increasing “burden of knowledge,” or the idea that as knowledge accumulates it becomes increasingly difficult for people and organizations to catch up to the current frontier. And as knowledge expands, expertise by necessity must become more narrow and discrete.

Where before one person might be able to operate at several different frontiers at once, that’s increasingly difficult. Multi-disciplinary teams are critical for success. But more importantly, a new order of knowledge generation and collaboration systems is required to exceed in the context of this burden of knowledge.

Confluence, amplification, and transformation

The information technology revolution has enabled a set of proliferating technologies that are only beginning to truly manifest in the market. Meanwhile, multiple other trends—in many cases influenced or enabled by technology innovation—are coming together to increase the pace of change in our society, economy, and world.

So the real driving force behind the increasing pace of disruption is the combination of multiple factors that combined result in a truly new economy—one that operates at a fundamentally faster pace than things used to. So buckle up, it's a whole new world out there.

Next: Read about What's So Different About Disruption?