The Age of Protocols

The past twenty five years or so have been driven by the Internet, mobile, and cloud computing—socially, economically, and even politically.

I believe the next twenty five years will be driven by a new set of forces that will result in fundamental changes to our economy and society. Those changes will be rooted in decentralized protocols and cryptographic assets. And just like the early days of the Internet, many people seem unaware of the scale and scope of the coming changes. I don’t pretend to fully understand where this wave is taking us. But I know the implications are truly staggering.

The driving forces that brought us here

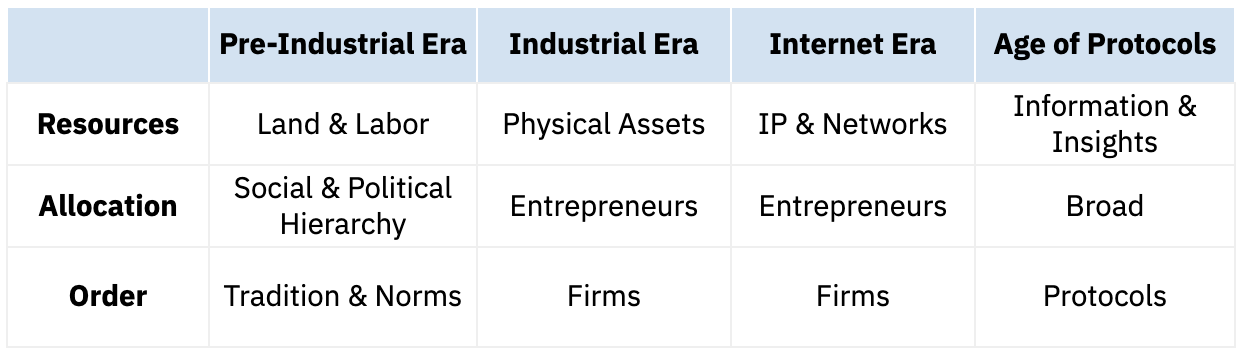

Putting this in perspective requires stepping back to look at a story arc that dates back to the late 1700s and the dawn of the industrial era. Let’s frame the discussion using three socio-economic elements:

- Resources: What are the most important economic resources?

- Allocation: How do we allocate the benefits generated with these resources?

- Order: What are the forces that maintain and enforce order and efficiency?

The Pre-Industrial Era

In the pre-industrial era, land and (control of) labor were the key sources of wealth and power. The benefits accrued to the social and political hierarchy, driven primarily by inheritance, who relied on tradition and norms to enforce order and achieve (modest) efficiencies. And that order was ultimately backed by sovereign nation states, and their claim to a monopoly on the legitimate right to use violence to enforce order.

The Pre-Industrial Era was the time of the landed gentry:

- Resources: Land and labor

- Allocation: Social and political hierarchy (e.g., landed gentry)

- Order: Tradition and norms, backed by nation states

The Industrial Era

The industrial revolution brought sweeping changes to the status quo. New technologies such as sanitation, medicine, electricity, and combustion engines enabled much greater productivity and new products and services. Populations began to gather in urban centers, creating new labor pools and new demand.

The volume and complexity of transactions grew exponentially. With them grew “the costs of negotiating and concluding a separate contract for each exchange transaction.” Neither independent artisans nor landed gentry were well suited to organizing and directing the scale and complexity of operations and assets required to satisfy all of this new consumer demand.

The rise of the firm

As a result, industrial firms arose, designed to internalize (and thus diminish) transactional and coordination costs and to achieve the economies of scale of asset holding and production required for success in the industrial economy.

The firms themselves were managed by entrepreneurs, the “person or persons who, in a competitive system, [took] the place of the price mechanism in the direction of resources.” (Ronald Coase) Division of labor, meanwhile, tended to subordinate workers to lower skilled and lower paid roles. Take, for example, Adam Smith’s description of the efficiency benefits of artisans at a pin factory being replaced by lower skilled workers responsible for single steps in a larger process.

In this new industrial world order, the sources of power and wealth transitioned from land to include a broader array of physical assets. The resulting value created was largely allocated to the entrepreneurs (think Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller) who coordinated the work and the disposition of corporate assets.

The Industrial Era was the age of firms and entrepreneurs:

- Resources: Physical assets

- Allocation: Entrepreneurs

- Order: Firms, backed by nation states

The Internet era

Over time, technological advances brought new players to the forefront. Financial, communications, and information technology firms began to replace industrials, mining, and utilities firms on the S&P 500.

But the Internet turned the knob to 11. It began the real transformation from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy. Sir Tim Berners-Lee (the creator of the Internet) imagined a web that was decentralized, permissionless, and driven by consensus. He believed that “you can’t propose something be a universal space and at the same time keep control of it.”

But that’s not the way it has worked out.

Web 1.0: At first, Sir Tim’s vision seemed to be playing out. The web was mostly about consumption, and there was little evidence of centralized control or manipulation. Users and companies consumed information created by a relatively small group of content creators. The earliest adopters were scientists and technologists. Of course there were commercial actors participating—I was one of them in the early 90s. But the early web was focused on distributing information and content, and in some cases effectuating transactions. It was raw, simple, and personal (think Geocities), and looked and felt fundamentally different from today—a place that no longer really exists (except in storage).

Web 2.0: By the late 90s, consumers began to engage and socialize on the web, creating an increasing trove of content and information. Web 2.0 wasn’t really about novel interface technologies or social media. It was about the transition of users from consumers to products—as in, the users became the product. Shoshana Zuboff (HBS professor) describes it adroitly as “surveillance capitalism.” Massive firms have “assert[ed] ownership rights over our personal information and defend that authority with the power to control critical information systems and infrastructures.”

The move from atoms to bytes only strengthened the newer firms that emerged to capitalize on it. After all, it’s much easier to scale digital goods and services than physical ones. The same applies to financial transactions.

The power of knowledge and networks is so great that key corners of our economy have become winner-take-all systems, or at the very least oligopolies. Displacing Google, or Facebook, or Amazon is a near-impossible proposition. As a result, the flywheel effects of power and wealth beget further power and wealth. That’s why we currently inhabit the world of JP Morgan, Blackstone, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Apple, and the like. The FAANG stocks alone account for a staggering 15% of the S&P 500.

The Internet Era saw a transition from physical to digital, but otherwise most of the system carried over from the industrial era:

- Resources: Intellectual property & networks

- Allocation: Entrepreneurs

- Order: Firms

A summary of the status quo

Our society and economy grew radically more complex starting in the late 1700s. Pre-industrial constructs were ill-equipped to manage that growth. A means of reducing transaction and coordination costs was required.

We turned to a new construct: the modern firm, and the entrepreneurs who managed them. Entrepreneurs took on the role of a central decision maker and arbiter for increasingly large and far flung organizations. Order was maintained by the firm and its centralized power to hire, fire, and compensate. Trust was laid at the feet of the firm and its leadership to make good decisions due to market forces. Given control of the purse strings, the entrepreneurs naturally allocated the bulk of the rewards to themselves.

I haven’t mentioned it yet, but governments had to step in to curb excesses (e.g., child labor) early in the industrial era. Over time, government involvement increased significantly as new challenges and dislocations occurred. Unfortunately, regulations over time often favored the loudest and most powerful voices in the room—the firms—at the expense of the masses.

The overarching theme of all of this? Centralization of wealth and power, backed by regulatory schemes that more often than not favor those with wealth and power.

The pros and cons of centralization

Centralization can dramatically reduce transaction and coordination costs. It can infuse clarity into what would otherwise be an extraordinarily complex system. The alternative can easily result in slow and watered down decisions (e.g., decision by committee), tyranny of the majority, and other problems. In that context, putting decisions in the hands of entrepreneurs can make sense.

But the growth of massive firms creates its own inefficiencies. The successful lobbying of telecommunications firms likely explains how the US can be so far behind other developed countries in terms of Internet and mobile infrastructure. Other regulated industries such as banking have seen relatively little innovation or efficiency improvements over the decades. Why does it cost so much and take so much time to wire money? Why are merchant credit card fees almost 3%? Why is it so hard to get a mortgage? Why do 1.7 billion people globally remain unbanked? It’s because centralized organizations occupy key positions of trust and control in the system, protected from fundamental disruption due to their scale and regulatory moats.

But disruption is increasingly pervasive, and even the largest incumbents can no longer ignore it. Even the tech giants are in the crosshairs. Naom Bardin’s story about Waze’s acquisition by Google is telling. He explains how, despite Google’s strengths, it was essentially impossible to disrupt within a large organization. In general, large firms are ill suited to disruption, which reduces their relevance and value in the modern economy.

In the meantime, social norms and awareness of the downsides of centralization are weakening the bonds that bind firms together. The badge of honor associated with working for a big tech firm has tarnished as awareness of their troubling behavior comes to light (e.g., the surveillance economy).

Perhaps the biggest problem with centralization is it’s very essence: aggregation of wealth and power in the hands of relatively few. Real wages—as measured by purchasing power—have barely grown in the past 40 years, even while we have seen widening income inequality. Perhaps that would be sustainable if it were an accurate reflection of the relative contributions between workers and large firm owners. But I think we all realize that it isn’t. The deck is stacked in favor of the haves.

The Internet brought us together, but it hasn’t yet achieved the higher goals we always suspected it could. We have become the product. Massive companies have too much control over what we experience online. Internet finance is too similar to pre-Internet finance, with bizarre inefficiencies, inequitable access, and highly concentrated wealth and power.

The powder is in the keg, and the wick has been lit.

The Age of Protocols

When anarchy is the alternative, centralization can look pretty good. But now there is an emerging alternative that will upend the status quo: cryptographic decentralized protocols.

These protocols replace trusted central authorities. That in turn means much greater efficiency and broader distribution of wealth and power. The genie is out of the bottle, and nobody will be able to stuff it back in again—not that they won’t try (more on that in an upcoming article).

The Age of Protocols is transitioning from away from a longstanding model built around firms and entrepreneurs:

- Resources: Information & insights

- Allocation: Broad

- Order: Protocols

When cryptographic assets (or “cryptos”) first came out, there was a lot of discussion about blockchains, often centered around how enterprise blockchain would help advance the interests of large firms.

As a technologist, I was skeptical. Distributed ledgers seemed a lot like a new approach to data storage that wasn’t otherwise intrinsically disruptive. A distributed ledger could have uses for enterprise, but it seemed to focus far too much on a specific technology versus the problems that require it. After all, there are well-known ways to store and validate shared information that don’t involve a blockchain. It turns out, that whole thing was a red herring.

The real play here is how decentralized protocols (using smart contracts) can in many cases replace the role of the firm in the modern economy. The essence of firms breaks down to protocols, which in turn boils down to rules of order. The entrepreneurs control the protocols within a firm, and enforce them through a combination of legal ownership rights and the power to hire, compensate, and fire employees and contractors.

Cryptographic protocols act similarly in that they force coordination of action and adherence to rules, but they do it through digital contracts that are automatically enforced, and require no particular centralization. As a result, entrepreneurs are no longer needed, or rather individuals can more effectively become their own entrepreneurs.

Governance can be collective and broad, and decisions are implemented and enforced automatically. Naturally, that leads to a broad and relatively fair allocation of power and wealth. It turns out, it also tends to lead to dramatic improvements in speed and efficiency. The way we coordinate and allocate value creation in our society is changing. It’s already starting to happen. And the implications are truly staggering.

The Rise of Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

It’s tempting—and common—to focus on digital currencies such as Bitcoin. It’s true, they will fundamentally alter our global fiscal and monetary systems. Governments will lose certain tools, controls, and oversight, no matter how hard they struggle to retain them (I’ll write more on that in an upcoming article).

But one of the most impactful areas where protocols are gaining traction is in the sphere of finance—DeFi, or Decentralized Finance. For decades, large financial institutions have made tremendous profits due to centralization (CeFi, or Centralized Finance). But they’re being disrupted (at the edges, for now) by faster, more adaptable, more efficient, and more equitable cryptographic protocols.

Here are just a few examples (of literally thousands) of cryptographic DeFi projects:

- MakerDAO, Aave, Compound, and others offer high yield instant lending backed by crypto assets (and presumably other assets over time)

- Uniswap, PancakeSwap, SushiSwap, and others offer decentralized exchanges with integrated automated market making capabilities

- Flexa, Matic, Lightning, and others offer fast, cheap, and scalable payments solutions

- Synthetix, Terra, Mettalex, and others offer synthetic versions of external markets (e.g., stocks, commodities, and more)

- Rarible, SuperRare, Nifty and others offer NFT (Non Fungible Tokens) used to represent ownership in—and facilitate transactions in—unique assets such as art, real estate, etc.

- USDT, USDC, DAI and others offer stablecoins pegged to fiat currencies to allow stability without requiring an offramp from the crypto infrastructure

Why Will DeFi Win?

DeFi is (or in some respects is on the path to be) fundamentally better than CeFi:

- Orders of magnitude faster and cheaper

- More adaptable and composable

- Fairer and thus more equitable

- Truly global, with greater liquidity

Orders of magnitude faster and cheaper

For the moment, DeFi has not achieved anywhere near peak efficiency. ETH (Ethereum) is the de facto standard for the smart contracts which underlie DeFi. But early architectural decisions combined with massive growth have led to transaction fees and times that are untenable in the long term. Although they’re still better than CeFi, all things considered.

In the meantime, massive resources are being allocated to improving speed and efficiency. Frameworks such as Matic, Polkadot, and Binance Smart Chain have arisen to address these issues, and even more transformative protocols are on the way.

Decentralized exchanges can already make and clear transactions—including massive ones—instantaneously for fractions of a penny. And users are no longer the product—no more front-running of sales to big hedge funds, and no lockups or lockouts due to centralized technical or margin failures.

We’re headed towards a system that will be multiple orders of magnitude faster and more efficient than existing financial systems, and in many cases that’s already true.

More Adaptable and Composable

Interoperability and permissionless composability of most cryptographic protocols will be decisive advantages for DeFi over CeFi. These open up innovation and problem solving opportunities that cannot be replicated in the slow, high friction world of centralized finance.

Many of the most successful DeFi projects are themselves composed of building blocks of other protocols. One example is Yearn, which automatically allocates assets to the protocols and places with the best staking ROIs. And it’s all done automatically, cheaply, and transparently at very low cost—no fund or portfolio manager required. This wouldn’t be possible without transparency and permissionless composability.

And it’s not limited to compositions designed by protocol builders. End users can compose their own solutions, too. For example, if I buy a microcap crypto asset, I can then put those holdings into a liquidity pool to earn interest on them. The pool tokens I receive can then be used as collateral for a loan to be used for other purposes. I would earn the difference between the liquidity pool returns and the loan costs, while still holding the original asset for appreciation. And I wouldn’t have to ask anyone for permission, fill out any paperwork, or even explain to anyone why they should trust me.

Solutions are also not limited to the finance world as we know it. Take flash loans, for example. Aaave is a platform that allows users to borrow crypto assets with no collateral, as long as they’re returned in the same atomic transaction. Suddenly, value arbitrages can occur with zero working capital; I can set up a purchase of one crypto asset that converts to another crypto asset (or more), and as long as I return the original amount “borrowed,” I don’t need any collateral or working capital. Anyone can now set up an arbitrage that might otherwise require billions of dollars in working capital.

As DeFi matures, the variety of composable protocols will multiply, and the combinatorial options will grow exponentially. This will result in dramatically faster innovation and much greater personalization. So while centralized finance players fight to keep their regulatory protections and shore up their defensible moats, the DeFi industry will be innovating right past them. Centralized finance won’t know what hit it.

Fairer and Thus More Equitable

The fees generated by DeFi activities (paid in cryptos) are generally spread among market participants based on their contributions of liquidity, computational power, optimization decisions and the like. That’s truly disruptive, if you think about it. An estimated 6% of global GDP goes towards centralized finance. All of that value will accrue to market participants instead of centralized financial institutions.

So instead of profits accruing to big banks and similar players, individual contributors to the crypto ecosystem are making high annual percentage yields on their assets—often north of 10% (and in some cases much, much more), while still being able to hold them for potential appreciation.

This opportunity is particularly important for a vast swathe of market participants who are largely excluded from the mainstream financial system. They, combined with other early adopters, will continue to expand and build out the system, and the resulting benefits will become increasingly attractive to more mainstream investors. Why put your money in a money market account that makes about nothing when you can make 10%+ at very low risk?

And don’t underestimate the power of fairness and equity. Vitalik Buterin, the creator of Ethereum, describes the importance of “soul,” and dismisses projects that are focused merely on monetary gain. It might be tempting to dismiss this as a utopian fantasy, but it’s rooted in very real social dynamics. One percent of the global population controls over half of global wealth. A tremendous number of people around the world are being excluded from the global economy. It even applies to American millennials, who entered the job market during the employment trainwreck post 2008. Many are still struggling with student debt loads.

So it’s unsurprising that the new generation tends to have a deeply cynical view of our financial system, and because they by-and-large aren’t the beneficiaries of it, a motive to reform it: “[n]early half of Gen Z and millennial respondents [feel] the U.S. economic system work[s] against them.”

On the level playing field of cryptos, the aggregate power of the have-nots totally overpowers the few centralized power brokers. Think twice before discounting the power of fairness and equity.

Truly global, with greater liquidity

DeFi and cryptos, unlike centralized finance, are truly global. Decentralization means that any local barriers imposed are little more than friction—like trying to stop a river by standing in it. People across the globe are putting in their dollars and cents, and the aggregate is greater than any firm or government could ever fight. The benefits are strong enough, and the system is so decentralized, that even monitoring it is essentially impossible, much less controlling it (more on this later in a separate article).

For now, it’s mostly early adopters who are benefiting from this reallocation of transactional costs to themselves. But as the market matures, and as user experiences become more accessible, the scale of market participation will grow dramatically, resulting in a steepening loss of volume and revenues for centralized financial institutions.

It’s increasingly easy to move assets into cryptos. And CeFi’s inexorable drive to increase short term profits will only increase capital allocations to crypto: wealth advisors, for example, won’t let this opportunity for new allocations and fees go to waste.

That leads us to what I call the “crypto ratchet.” Once assets land in the crypto economy, there are tremendously powerful incentives to keep them there. Very high risk-adjusted returns, easy customization of the risk-reward ratio, flexible timing, and easy liquidity are incredibly hard to deny. You can even move cash out of cryptos without actually taking it out using crypto lending platforms. In that case, DeFi remains the real home base for your assets, and CeFi is left with the scraps.

As DeFi siphons volume away from CeFi, it will create an imbalance of opportunities that will accelerate the transition to DeFi. Over time, DeFi’s liquidity pool and breadth of offerings will be orders of magnitude greater than any firm or centralized marketplace could provide.

The market is now the world.

Not So Fast!

All my predictions notwithstanding, I’m well aware that we are in the very early days of web 3.0 and DeFi. In many respects it’s a spaghetti mess:

- Rapid growth means that the primary level 1 protocols are slow and expensive, and cannot efficiently handle current transactional volume much less anticipated growth (e.g., high “gas” fees)

- Most of crypto is scary and inaccessible to mainstream users—“the lunatics (technologists like me) are running the asylum,” as I like to say

- Immature auditing and security controls mean that taking full advantage of DeFi can expose users to risks of fraud and theft (e.g., rug pulls)

- Lack of regulatory clarity adds uncertainty to the mix, making it more difficult for conservative consumers and large mainstream organizations to adopt

- Decentralization comes with its own set of problems including coordination challenges (e.g., too many cooks in the kitchen) which manifest as competitive hard forks for example

But you could have said much the same about the early Internet. And it’s precisely for all the reasons above that there exists a near term opportunity to create truly exceptional value, and be a part of something that is fundamentally changing our economy and society.

The Next 25-Year Cycle

I believe this is nothing less than a fundamentally different web 3.0. And likely much more: decentralized protocols will define the next 25 years of our economy and society. This is an inflection point. This feels as big as—or bigger than—the Internet did in the early 90s when I started my first company.

Web 3.0 is the age of protocols: decentralized autonomous protocols are replacing the role of large firms. Power and wealth will be redistributed based on an entirely new paradigm driven by individual and small group contributions. Infrastructure and knowledge will rapidly democratize, further undermining the competitive advantages of large firms. We the people own web 3.0. Let that sink in. We’re owned by web 2.0. But we own web 3.0.

We the people own web 3.o

The composability and permissionless infrastructure of decentralized protocols will reduce the effectiveness of network effects, leading to faster adoption of new systems and technologies and an increasingly frantic rate of social and economic change. Large firms, and in particular centralized financial institutions, already under pressure from disruptive technologies, will be further weakened. As my partner John Sviokla says, the “world is becoming more computable.” The reach and impact of all of this is extending to everything.

The most massive wealth transfer human society has ever seen has begun. It favors the younger generation and early adopters, and disfavors established wealth focused on traditional assets and fiat currencies. Some established wealth has gotten in early enough to ride the new wave, but the vast majority will miss the boat.

Social assets will transition, too, in favor of charismatic influencers and crypto-entrepreneurs. We’ve seen that story before, first with the industrial barons, and then later with the tech entrepreneurs. But this time, things will be far more democratized. We can see an early glimmer of it happening with the rise of individual influencers on Tik-Tok, YouTube, and Twitter.

There have been countless questions about Bitcoin’s role in our economy. Is it a currency? Is it the new digital gold? I think that’s backward-looking. It's much bigger than any of that. Bitcoin is the reserve currency for the new economy that’s replacing centralized finance. So the real question is, what will become of traditional finance? And the current web version of the web? I think the writing is on the wall, and it isn’t pretty.

We all have two choices: embrace the age of protocols, or be left far behind.