The AI Inflection Point

AI is at an inflection point. It can now design, create, persuade, and more. What does this mean? How disruptive will this be?

AI-based disruptors such as ChatGPT are at an inflection point. What are the implications for incumbents? Investors? Entrepreneurs? Asset allocators?

On November 30, 2022, OpenAI launched a new version of ChatGPT, which has captivated millions of users. It’s a leading example of Generative AI, a category that is going to fundamentally transform our society and our economy. Read on for a discussion of what, why, and how.

Summary

Machines continue to increase the scope of analytical tasks they perform better, faster, and cheaper than humans.

Now they’ve come for our creative capabilities—writing, problem solving, art, photography, design, research, and more. And they’re quickly making inroads on social skills. In many cases, they’re already as good as—or better than—most of us.

As Manifold partner John Sviokla pointed out in 2020, we’re entering the Bionic Era, a sort of new Industrial Revolution. Except this time it’s not just about labor automation—it’s about computability, the automation of knowledge work.1

Our world is quickly becoming “computable.” Work and play will be transformed. As with prior technological waves, jobs will be displaced, incumbents will be replaced, and new industries will be created.

But there’s a chance—and some evidence—that this time the disruption will be much more far reaching. When AI is better, faster, and cheaper at most knowledge and social tasks, displaced jobs may very well be replaced by AI, not new human jobs. Meanwhile, the scope of labor automation will expand as AI and robotics continue to advance.

The implications of this are hard to overstate. It’s almost certain that we’re facing a period of turbulent change and emergent paradigms. It’s quite possible that the upcoming creative destruction will exceed anything anyone has seen before.

Let’s explore what this means for incumbents, investors, and entrepreneurs.

What’s happening?

The concept of artificial intelligence has been around for decades. And although “true” AI (Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI) has yet to arrive, advances in Analytical and Generative AI suggest that we’re in the very early stages of a steep inflection point.

AI or Artificial Intelligence is technically a misnomer, and those in the industry often use more specific terms such as ML (Machine Learning) or D&A (Data & Analytics) instead. When AI is used, it’s a shorthand for convenience or so as not to confuse people.

If you’re seeing a lot of chatter about AI right now, it’s likely due to recent developments2 in Generative AI that are capturing the imagination of many early adopters. The writing and images being generated represent shocking advances in capabilities over the past few years. It might be easy to dismiss this all as a distraction, but that would be a mistake.

Analytical AI has begun to transform jobs and industries. But now machines have come for the jobs that require creativity, problem solving, and social skills. In some cases, they’re already as good as—or better than—most of us. And the implications for our economy and society are staggering.

In 2013, researchers estimated that 47% of jobs were at risk due to AI over time, but that “creative intelligence tasks, and social intelligence tasks are unlikely to be substituted by computer capital over the next decade or two.” 3

I present for your enjoyment the following images, which were created entirely by AI. Each was created in moments, simply by typing descriptive words into an AI image creator.

The following were all created in seconds entirely by Generative AI tools

It’s not (at all) limited to 2D images, either. How about this NeRF scene built in real time from four partial images:

The scene can be instantly navigated in 3D, and includes many details that were not featured in the images it was built upon—AI interpolated and recreated everything that was necessary.

And then there’s Cicero, developed by Meta AI, which has achieved 90th percentile human level performance in the game of Diplomacy, which requires deep interpersonal, social, and negotiation skills.4

“Diplomacy has been viewed for decades as a near-impossible grand challenge in AI because it requires players to master the art of understanding other people’s motivations and perspectives; make complex plans and adjust strategies; and then use natural language to reach agreements with other people, convince them to form partnerships and alliances, and more. CICERO is so effective at using natural language to negotiate with people in Diplomacy that they often favored working with CICERO over other human participants.” 5 [emphasis added]

Or Pluribus, which can consistently beat the best poker players in the world despite the complexities of bluffing and incomplete information.6

And here’s OpenAI’s ChatGPT7 adroitly explaining three different categories of AI:

“Reactive AI is the most basic type of artificial intelligence, which focuses on reacting to stimuli in the environment without the ability to form memories or make decisions based on past experiences. This type of AI is often used in simple applications that require fast responses but do not need the ability to learn or adapt.”

“Analytical AI, also known as cognitive computing or computational cognition, is a branch of artificial intelligence that focuses on developing algorithms and systems that can process, analyze, and understand complex data in order to make decisions, solve problems, and perform other tasks that typically require human-like intelligence. This type of AI is often used in applications such as natural language processing, computer vision, and decision-making systems.”

“Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that focuses on generating new content, such as images, text, or music, based on a set of input data. This is typically done using machine learning algorithms, such as deep learning neural networks. The way generative AI works is by training a model on a large dataset of existing content, which allows the model to learn the patterns and characteristics of the data.”

And if that’s not enough, how about this verse written in the style of the King James Bible explaining how to remove a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR:

I’m sorry, I simply cannot be cynical about a technology that can accomplish this. pic.twitter.com/yjlY72eZ0m

— Thomas H. Ptacek (@tqbf) December 2, 2022

And there’s already so much more: software code, articles, research papers, music, speech, designs, molecules, and more.

The Bionic Era

Manifold Partner John Sviokla described the Bionic Era in his 2020 article:

“We are in a new era, which I call the Bionic Era, and it’s as powerful and pervasive as the industrial era before it. In the bionic era, we have a new blend of people and machines both doing and thinking together. Where the industrial era automated physical work, the bionic era automates symbolic work – thinking, perceiving and judging, blending with the advances of the industrial era in a dynamic and powerful way.” 1 [emphasis added]

He described the increasing variety of activities becoming “computable.” What’s key about Generative AI is that it dramatically expands the range of what is “computable” to include much of what knowledge and creative workers have traditionally done.

Claude Shannon developed Information Theory in the late 1950s, which describes information as the opposite of entropy: the reduction of uncertainty.8 Explaining the possibilities of AI from this perspective, it’s natural to think of AI as part of a bionic symbiosis with humans.

But because AI can be layered, integrated into decision making systems, and incorporated into hardware, it’s also potentially much more than bionic. It can increasingly function independently, affecting the world around it both directly and indirectly.

That means we might be in a very different place than prior eras of creative destruction. Instead of merely displacing human jobs, there’s a good chance AI might permanently destroy them.

And yet deep challenges remain

The current manifestations of AI have weaknesses. Some are deeply flawed. And our society may not be entirely prepared for AI, or at least it may not desire to be. To put it simply, generative AI is not quite ready for mainstream use. Legal uncertainties, inconsistent quality, and improper use conspire to limit the breadth of use likely for the very near term.

Here are some of the most important weaknesses and barriers to AI performance and adoption.

Training data, copyright, and questions of fair use.

Creatives whose work is being emulated have complained that GAI isn’t creative: it’s just copying—regurgitating pieces and parts of things that it “stole” from humans. But that’s not a fair description. The “parts” involved are concepts, rules, and styles and not a collage of prebuilt parts. Even when GAI produces stock photo watermarks, it’s because they were trained to reproduce them. The underlying images are new, and not copies of an existing image.

Explore the way generative AI works, and it’s clear that it creates novel outputs informed by prior styles and themes—but nonetheless new.9 And that’s how the vast majority of human creativity works. The origin of the quote “good artists borrow; great artists steal” itself10 lays bare the truth of how we layer creativity: the origins are layered and muddy, demonstrating layers of building upon pre-existing concepts that culminated in the current version.

It’s difficult to determine the ethical approach to AI appropriation of styles or content elements. From a practical perspective, the use of copyrighted works for AI training purposes is likely covered by the fair use doctrine in the US, although even that isn’t entirely clear. The reproduction of works that closely resemble copyrighted works is far more fraught with risk.

Implicit bias

AI reproduces biases found in its training sets. So, if you ask for an image of a teacher, the results will almost certainly feature a woman. Ask for a doctor, and you’ll get a man. Virtually all of the biases you can think of tend to manifest in the outputs created by Generative AI.

And this is particularly challenging for the current state-of-the-art AI because it’s often difficult to understand the source being used to generate content. As a result, bias can be hard to trace, track, and identify.

GAI can be convincingly wrong, or quality can be inconsistent

Generated images sometimes look awkward, and human hands often come out disfigured or with an incorrect number of digits. ChatGPT sometimes happily asserts patently incorrect facts or logic. And its writing tends to be somewhat bland, with an intangible artificial feel.

There’s also a very valid question about the level and nature of creativity exhibited by GAI. At present, it certainly seems that GAI is capable of Improbable Creativity, but much less clear (and less likely) that it’s currently capable of Impossible Creativity. The former involves “improbable combinations of familiar ideas,” while the latter requires “novel ideas that, relative to the pre-existing conventions of the domain” could not exist.9

And yet, Stephen Marche argues in The Atlantic that ChatGPT’s writing is “frankly better than the average MBA at this point.”11 The image generators are wildly better than the average human at generating art and photos. And they’re far faster and more flexible than any human artist.

Prompting, awkward interfaces

Generative AI is another instance of “letting the lunatics run the asylum” as I like to say: let the engineers and data scientists build it, and it’s likely to have an awkward and overly technical interface. That’s certainly true for much of GAI at this time. Rendering high quality images requires careful prompting, to the point that certain people are describing themselves as “prompt engineers.” That’s something that will likely resolve itself naturally, but in the meantime will serve as friction for broader adoption.

Access to data for training

Most Generative AI relies on massive data sets. ChatGPT, for example, uses a Large Language Model (LLM). While there’s certainly diminishing returns at a certain point, these models still require fantastic amounts of inputs to be useful. Finding appropriate, clean, and tagged data that can be appropriately used will certainly limit progress in the near term.

Terrorism and anarchy

If you know how to circumvent certain filters (it’s not difficult), you can get ChatGPT to tell you how to make bombs or hot wire a car. It can even tell you how to wage a successful terror campaign or build biological weapons. While this information in the end came from existing public sources, the accessibility and clarity of its delivery through ChatGPT certainly presents challenges for our society.

Explicit content, child pornography, and deep fakes

Generative AI can be quite easily used for deeply inappropriate purposes. It’s almost impossible to stop this behavior: anyone with relatively modest technology skills can run GAI programs locally and privately on their own hardware without any filters or watermarks.

Privacy infringements, security weaknesses

GAI has such a broad and interconnected set of data that it can inadvertently reveal private information that would otherwise be hard to access. If you ask GAI (the right way) how to hack a system, there’s a good chance it will tell you precisely how to do it. And if someone does crack a private GAI system, it might be extremely difficult to track down what they’ve done or learned by doing so.

Plagiarism and cheating

GAI makes to trivial to cheat on tests and papers. Simply ask it to write you a college paper, and you’re likely to get something good enough to get you an B- on a typical paper.11

And that’s only going to get easier and higher quality in the coming years. It’s likely that GAI will write papers better than any human within five years—or perhaps fewer.And while there’s talk of tokenized AI hashes to identify whether specific content came from an AI, that approach probably isn't technologically sustainable.

The dawn of a new era

It’s easy to dismiss Generative AI by pointing out its current weaknesses. But none seem likely to present fundamental barriers to AI. Copyright, for example, will likely be overcome through small training sets, large open source training sets, and the inexorable market demand pulling generative AI forward. Another example is our portfolio company PowerNotes' patent-pending proof of authorship to combat cheating.

AI technology is improving at a breathtaking pace, and the social, economic, and geopolitical forces acting as tailwinds for AI adoption mean that it’s a likely question of when, not if, generative AI will become broadly adopted.

The fact that it's people with college educations getting replaced this time is nothing new. Automation has been moving up the "food chain" the entire time. It started out replacing donkeys.

— Paul Graham (@paulg) December 13, 2022

We are clearly in the dawn of a new era.

What’s coming down the pike?

It’s tempting to consider possibilities based on current state technology. But sometimes—and in this case it seems to be so—the tech improves so quickly that predictions need to be predicated on future capabilities.

As I’ve described elsewhere, layers of technology are combining to create emergent new opportunities—and threats. Generative AI and its close cousin Analytical AI are just one of a number of technologies that are creating a whole new world ahead of us.

At a minimum, unprecedented job displacement

This is far from the first time broadly applicable technologies have fundamentally changed our social and economic realities. Robert Gorden described just how much the five Great Inventions—electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication—changed our world.12 He argued that by comparison innovation going forward, and in particular based on information technology, will be “incremental and [slow].”

The authors of the book Prediction Machines believed predictive AI would function primarily to empower white collar workers to perform their jobs more efficiently.13 Noah Manion and Roon have argued that “AI doesn’t take over jobs, it takes over tasks.”12

Dystopia: "Robots will do half of your jobs"

— Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇦 (@Noahpinion) September 23, 2018

Utopia: "Robots will do half of your job"

That's a reasonable presumption. Industrial revolution led to task automation that reduced employment in many areas, while creating even more new jobs (engineers, machinists, repairmen, conductors, managers, and financiers).15

Agricultural mechanization in the US similarly created new clerical, services, and manufacturing jobs.15 So, just as the industrial revolution created more jobs than it destroyed, we may be heading into an era—a Bionic Era—where AI and other tools serve primarily to enable human superpowers.

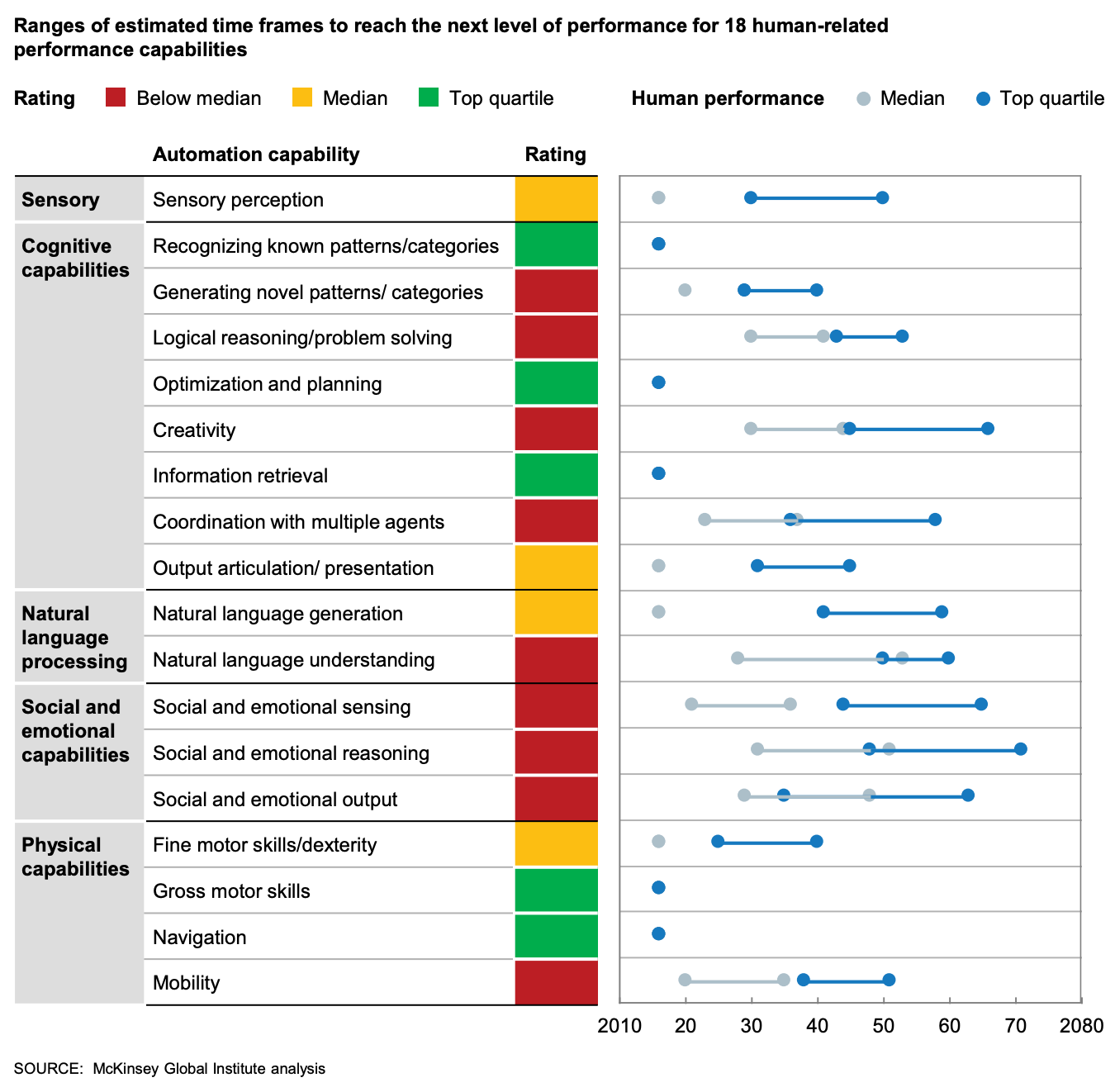

But the scope and scale might be far more than anyone living today can recall. As of 2013 machines were expected to displace (or eliminate) 47% of jobs.3 In 2017 McKinsey published a report estimating that 51% of work hours in the US were susceptible to full automation.16

Let’s assume a 30 year timeframe for this (roughly what McKinsey estimated), even though that seems too long given the pace of AI innovation and the economic potential associated with successful adoption. Based on roughly 165 million US workers, that means 5.5 million new workers out of jobs and $100 billion in displaced wages per year.

By 2030 that could mean 44 million lost jobs, and $800 billion per year in lost wages. How many will find new jobs? How many companies will struggle and fail in the context of a new workforce and technology paradigm?

This would be a level of creative destruction unfamiliar to any living person. And yet there are compelling reasons to believe the reality will be far worse.

Likely pervasive job destruction

The scope of tasks that machines can perform as well or better than humans has increased significantly since estimates surfaced that AI would replace half of all jobs. And AI is in almost every case orders of magnitude faster and less expensive than a human performing the same job.

“... the displacement effect of automation has been counterbalanced by technologies that create new tasks in which labor has a comparative advantage.”15

If job replacement presumes new tasks in which labor has a comparative advantage, which are those tasks? Machines have in many cases surpassed human analytical abilities. Now they’ve come for our creative, problem solving, and social capabilities. Given the unit economics, it’s hard to imagine a world where GAI doesn’t fundamentally change the dynamics of our entire economy.

There’s some evidence job destruction started happening thirty years ago. As of 2019:

“[T]here has been a slowdown in the growth of labor demand over the last three decades and an almost complete stagnation over the last two… the sharp slowdown of US wage bill growth over the last three decades is a consequence of weaker-than-usual productivity growth and significant shifts in the task content of production against labor.”15

I argue that just as it took decades for the impact of the Great Inventions to fully materialize, information technology will only culminate over time.17 And the advent of GAI suggests it’s going to be a doozy. And we haven’t even taken into account quantum computing, CRISPR, nanotechnology, and more.

And it’s happening far faster than expected

All of this occurs in the context of technologies that are advancing at a breathtaking rate. OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT was founded in 2015, and released their first version in 2018. ChatGPT 4 is rumored to be around the corner, and to represent an order of magnitude improvement over the existing ChatGPT 3.5 (the current publicly available version). Image generators are improving on a monthly and sometimes even weekly basis.

Progression of quality for diffusion image generation in under four years

Even experts in the field have consistently underestimated the pace and breadth of innovation in AI. It seems quite likely that Generative AI will generate higher quality results in most areas than even highly trained humans within five years. Arguably, it’s already there.

In 2004, researchers estimated that driving in traffic was “insusceptible to automation,” and yet six years later Google announced the release of early fully autonomous cars.3 As of 2022, fully autonomous taxis are operating in several cities across the world.

The research which called for ~50% job automation over the next thirty years failed to predict the pace of innovation in the AI space. McKinsey estimated that AI might achieve 25th percentile human quality somewhere between 8 and 50 years from now.16

It certainly seems that AI has already achieved some or all of these, or at least is on the cusp of doing so—between 8 and 50 years ahead of schedule.

And as described previously, we're benchmarking against technology that's about to be replaced with something radically more powerful, so things could be further along than we realize.

What are the implications?

What are the implications? What are the opportunities? How can we as investors, entrepreneurs, and asset allocators thrive going forward? What does it mean for incumbents and traditional models? It’s not certain by any means, but it’s possible we’re looking forward to:

- 75% of jobs being displaced

- Within 15 years, not 30

- With 50% of those permanently gone

- …. A post work economy?

Whatever the case, it seems that virtually everyone—employers, employees, investors, entrepreneurs, and our nation states—are facing a period of face melting disruption for at least the next twenty years. For some it will mean incredible opportunities. For others it will mean destruction and pain. Few will remain untouched.

A fateful time for incumbents

The average tenure on the S&P 500 has dropped from approximately 75 years to about 12. Creative destruction is coming for incumbents, and it’s not letting up. In fact, it’s likely just getting started.

Arguably incumbents have at least two key advantages in the coming times: access to data, and the prospects for decreasing costs and increasing margins using AI for their existing business models. But these are unlikely to be sufficient. Inertia, protecting the proverbial Golden Goose, system complexity brought on by new possibilities, and trends disfavoring large firms all combine to pose existential threats for most large companies.

Even the “new” tech companies such as Google are vulnerable. Using ChatGPT makes it crystal clear that Google’s cash cow search business can’t remain as it is. And while Google has some of the best AI talent on the planet, I’d hesitate to bank on their ability to destroy their own business model and replace it with a new one while flying their $250 billion plane. At the same time, the economics might be fundamentally against them: there’s at least one estimate that it would cost $50 million now (and much less in the future) to build a large language model generative Q&A system to threaten Google.

Established companies are designed to operate known business models using well understood technologies. They’re good at innovation, but not disruption. The same things that make them good at the former tend to make them fail at the latter. I explain more in my article on “How Great Companies Get Disrupted.”

The broader implications for firms—as in the Coase Theorem of—are similarly dire. AI eliminates friction, accelerates tasks, and likely destroys jobs. As a result, larger firms will have declining relevance in the new economy. And given the speed with which all of this is happening, many will fail to—or be fundamentally unable to—adapt more quickly than they become insolvent.

We saw something similar happen to General Motors, which went from employing almost one out every hundred US workers, to insolvency and eventually bankruptcy. For decades, their ability to centrally coordinate a massive, distributed workforce and far flung assets conferred competitive advantage. But over time, lean manufacturing methodologies, new supply chain modalities, and their organizational cruft eliminated their competitive advantage, turning it into a weakness. I suspect much the same will happen across industries, even to the most successful and long-lived companies.

I don’t believe any established company is safe. The largest and most established are likely the least so.

Conclusion

AI will definitely displace a large percentage of jobs, including knowledge work and creative jobs. And the breadth of displacement is likely to be far greater than anything we have seen to date with the possible (but far from certain) exception of the Industrial Revolution.

And this time the disruption will occur much, much more quickly than anything we have seen before. Artificial Intelligence technology is moving far faster and further than even experts predicted as recently as a few years go. New Generative AI capabilities in creativity, social skills, and precise motor control have likely brought forward AI disruption by 10+ years.

The breadth and depth of AI capabilities, combined with speed and unit economics may mean that most of the jobs displaced are not replaced by humans, but rather by more AI.

Either way, we’re at the cusp of a deeply disruptive and transformative period for our economy and society. So, the real question is: what’s not going to be deeply disrupted. It’s going to be an economic bloodbath like few living people have ever seen.

Generative AI isn’t quite ready for prime time, but we're not ready for AI, either. Now is the time to act.

Coming soon: Opportunities and strategies for surviving and thriving in the context of AI disruption.

Sources:

- Sviokla, John. “’Law of Computability’ Powers the Bionic Era”. Insurance Thought Leadership, 23 Aug. 2020

- Interestingly, the underlying tech is now two years old, and a substantially superior version is reportedly imminent. The recent excitement is due to a more accessible and usable UX.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt and Osborne, Michael A., “The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?”, 17 Sep. 2013

- Benj Edwards - Nov 22, 2022 11:32 pm UTC. “Meta Researchers Create AI That Masters Diplomacy, Tricking Human Players”. Ars Technica, 22 Nov. 2022

- "CICERO: An AI Agent That Negotiates, Persuades, and Cooperates With People”. Meta AI

- "Facebook, Carnegie Mellon Build First AI That Beats Pros in 6-Player Poker”. Meta AI

- Try it yourself at https://chat.openai.com/chat

- Hacker, Robert. “Generative AI: Every Problem Is an Information Problem”. Medium, Medium, 8 Dec. 2022

- Boden, Margaret A. “Creativity”. Artificial Intelligence, Elsevier, 1996, pp. 267-91

- “Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal”, Quote Investigator, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2013/03/06/artists-steal/ , which demonstrates the muddy origins and many, many layers and versions of this quote which itself was essentially stolen

- Marche, Stephen. “The College Essay Is Dead”. The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Dec. 2022

- Gordon, Robert. “The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War”. Princeton University Press; Revised edition, 29 Aug. 2017

- Agrawal, Gans, and Goldfarb. “Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence”, Harvard Business Review Press, 17 Apr. 2018

- Smith, Noah, and Roon. “Generative AI: Autocomplete for Everything”. Generative AI: Autocomplete for Everything, Noahpinion, 1 Dec. 2022

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 2, American Economic Association, May 2019, pp. 3-30

- “A Future That Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity”, McKinsey Global Institute, Jan. 2017

- Dwyer, Joseph. “The Flywheel of Disruption”, joedwy.com, 9 Mar. 2021